Degrees & Certificates

Historically Black University in Louisiana

Students to faculty ratio

Our Roots

After the Civil War, New Orleans experienced an influx of formerly enslaved people. One institution that sought to serve them was Thompson Biblical Institute, founded in 1866 to train freedmen to become ministers. Finding it difficult to philosophically meet the developing Black community where they were, Thompson became a biblical department within Union Normal School in 1869. Union, which was run by the Freedmen’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church (now the United Methodist Church), was established to train African-American teachers, providing a significant need throughout the South. Along with that need came a demand for higher education, which led Methodist Episcopal Church officials to convert Union to New Orleans University in 1873.

Among other institutions that were part of this network was Gilbert Academy, which was incorporated into New Orleans University in 1919. Also part of that ecosystem was Flint Medical College, founded in 1889 to meet the demand for trained Black nurses. Later, the University absorbed Phyllis Wheatley Sanitarium, founded in 1896. The sanitarium was renamed Sara Goodridge Nurse Training School. When lack of funding threatened Flint Medical College’s existence, it joined Goodridge to become Flint-Goodridge Hospital in 1916.

Among other institutions that were part of this network was Gilbert Academy, which was incorporated into New Orleans University in 1919. Also part of that ecosystem was Flint Medical College, founded in 1889 to meet the demand for trained Black nurses. Later, the University absorbed Phyllis Wheatley Sanitarium, founded in 1896. The sanitarium was renamed Sara Goodridge Nurse Training School. When lack of funding threatened Flint Medical College’s existence, it joined Goodridge to become Flint-Goodridge Hospital in 1916.

The same year of the founding of Union Normal School, Straight University was founded with support from the American Missionary Association of the Congregational Church (now the United Church of Christ). The University was named for businessman and philanthropist Seymour Straight who partnered with the American Missionary Association to provide higher education opportunities for African Americans, post-emancipation. In 1905, Straight University became Straight College.

A New Era

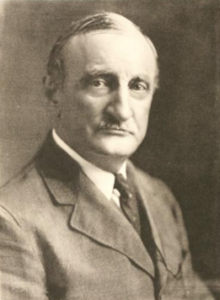

In 1928, Straight College president James P. O’Brien made an appeal to businessman Edgar B. Stern for financial support. O’Brien’s request sparked interest from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, the General Election Board of New York and several prominent New Orleanians. On June 6, 1930, the newly formed board of trustees for the new institution proposed a charter for the opening of Dillard University, named for James Hardy Dillard, an educational reformer who promoted racial harmony. The University’s seal, which was designed by Dillard, includes the motto “Ex Fide Fortis,” an anchor to represent steadiness, and scales to represent justice. The motto was originally translated by Dillard as “From Confidence Courage.”

In 1928, Straight College president James P. O’Brien made an appeal to businessman Edgar B. Stern for financial support. O’Brien’s request sparked interest from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, the General Election Board of New York and several prominent New Orleanians. On June 6, 1930, the newly formed board of trustees for the new institution proposed a charter for the opening of Dillard University, named for James Hardy Dillard, an educational reformer who promoted racial harmony. The University’s seal, which was designed by Dillard, includes the motto “Ex Fide Fortis,” an anchor to represent steadiness, and scales to represent justice. The motto was originally translated by Dillard as “From Confidence Courage.”

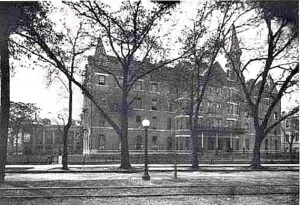

Opening its doors in 1935, Dillard University was established to serve as an educational center of excellence in the South. The campus, which remains in its original location, had the unique attribute of being the first HBCU with a sound architectural plan. The new liberal arts university subscribed to the DuBoisian notion of disciplining the mind and stimulating both “the creation of ideas and the development of the higher qualities of the individual.”

Prior to Dr. Ford’s appointment, seven presidents and four interim presidents have led Dillard University.

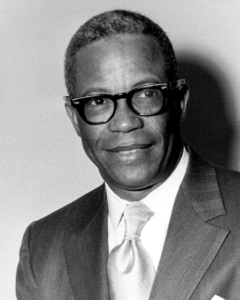

1941-1969

He guided Dillard through the turbulent decades of World War II, the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power movement. Part of his legacy was solidified by capital improvements. The beautiful 33-acre consisted of Rosenwald Hall, Kearny Hall, Hartzell Hall, Straight Hall, Howard House, the President’s Residence and several small cottages for faculty. During his administration, the University added: Henson Hall, named for Matthew Henson; Stern Hall, named after Edgar B. Stern; Lawless Memorial Chapel, dedicated to its benefactor Alfred Lawless Jr. and his father Theodore K. Lawless; and the Will W. Alexander Library. Under his leadership, Dillard gained membership to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools in 1958.

Dent also proved to be a pioneer. Having proven himself to be an effective superintendent of Flint-Goodridge Hospital, Dent declared that “a nursing program in Dillard University should develop better persons as well as better nurses; persons who will provide leadership in an increasingly important profession.” Through Flint-Goodridge, African Americans had received much-needed care at affordable costs which included Dent’s nationally acclaimed “Penny-a-Day” insurance plan at $3.65 per year. Therefore, establishing a nursing program was a logical next step. Dent’s vision became a reality in 1942 when Dillard became the first institution of higher learning in Louisiana to establish an accredited baccalaureate program in nursing. A key figure in developing Dillard’s nursing program was Rita E. Miller, a Black nurse who understood and championed professional nursing education. Miller devised a rigorous five-year academic program with high admission standards which led to the program receiving full accreditation from the National League for Nursing in 1952. Dent was also responsible for Dillard becoming a founding member of the United Negro College Fund in 1944.

Dent also proved to be a pioneer. Having proven himself to be an effective superintendent of Flint-Goodridge Hospital, Dent declared that “a nursing program in Dillard University should develop better persons as well as better nurses; persons who will provide leadership in an increasingly important profession.” Through Flint-Goodridge, African Americans had received much-needed care at affordable costs which included Dent’s nationally acclaimed “Penny-a-Day” insurance plan at $3.65 per year. Therefore, establishing a nursing program was a logical next step. Dent’s vision became a reality in 1942 when Dillard became the first institution of higher learning in Louisiana to establish an accredited baccalaureate program in nursing. A key figure in developing Dillard’s nursing program was Rita E. Miller, a Black nurse who understood and championed professional nursing education. Miller devised a rigorous five-year academic program with high admission standards which led to the program receiving full accreditation from the National League for Nursing in 1952. Dent was also responsible for Dillard becoming a founding member of the United Negro College Fund in 1944.

Under Dent, Dillard’s national and international profile as a liberal arts institution grew. Part of that growth was attracting notable guest speakers as part of his Edwin R. Embree Memorial Lecture Series which saw figures as Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall and Ralph Bunche. Other visitors included Mary McLeod Bethune, Haile Selassie, Martin Luther King Jr., Jackie Robinson, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes and Matthew Henson.

Dillard came to play a role as one of New Orleans’ critical civic anchors. Behind the scenes, Dent played a part in negotiating race relations throughout the city. He worked with Mayor deLesseps S. Morrison on desegregating New Orleans’ public services while promoting University events that spoke to Black identity and pride. Most notable of those events was Dillard’s 1968 Festival of Afro-American Arts. All told, Dent guided Dillard through World War II, the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement.

1969-1973

The series was designed to “bring to the presence of Dillard University students and the New Orleans community a series of men and women who have made distinctive achievements in their own lives and who are themselves living models of the kind of excellence to which our students aspire and which our community should always respect.” The lecture series brought to campus key figures such as Benjamin Elijah Mays, Etta Moten Barnett, Aaron Douglas, Arna Bontemps and A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.

women who have made distinctive achievements in their own lives and who are themselves living models of the kind of excellence to which our students aspire and which our community should always respect.” The lecture series brought to campus key figures such as Benjamin Elijah Mays, Etta Moten Barnett, Aaron Douglas, Arna Bontemps and A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.

What posed a threat to Butler’s philosophy and direction was a larger issue that threatened Dillard in addition to other HBCUs. Large research institutions had begun offering Black students financial incentives, therefore, the board of trustees believed that there was a need to transform its curriculum to meet the needs of the University’s changing student body. Such changes clashed with Butler’s ideal of a traditional, classical education, so he resigned in November 1973. Dr. Myron F. Wicke was then selected to serve as acting president until 1974 when Dr. Samuel DuBois Cook became Dillard’s fourth president.

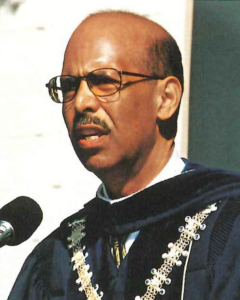

1974-1997

Cook had also been a Morehouse College classmate and friend of Martin Luther King Jr., and he had served as chair of Atlanta University’s political science department.

Recognizing that students required preparation for an increasingly competitive international and multicultural marketplace, Cook set out to expand Dillard’s offerings. In 1989, Cook created the Dillard University National Conference on Black-Jewish Relations from which sprang the Dillard University National Center for Black-Jewish Relations. He added the Japanese studies program in 1990 to prepare students for business and international relations opportunities. The Japanese studies would be the first of its kind at an HBCU and Dillard University National Conference on Black-Jewish Relations was the only one of its kind.

Recognizing that students required preparation for an increasingly competitive international and multicultural marketplace, Cook set out to expand Dillard’s offerings. In 1989, Cook created the Dillard University National Conference on Black-Jewish Relations from which sprang the Dillard University National Center for Black-Jewish Relations. He added the Japanese studies program in 1990 to prepare students for business and international relations opportunities. The Japanese studies would be the first of its kind at an HBCU and Dillard University National Conference on Black-Jewish Relations was the only one of its kind.

The Cook years saw other significant gains. The number and percentage of faculty members holding doctoral degrees increased. Cook also raised the requirements for admission, increased student enrollment by 50 percent, raised significant funds to improve the campus and facilities and expanded student services. In the process, alumni engagement grew and he increased the endowment from $5 million to more than $40 million.

Cook’s mark remains at Dillard in other ways. He served as the chair of the Presidents of the United Negro College Fund during his time at Dillard. He named the historic Avenue of the Oaks for longtime trustee and racial equality advocate Rosa Keller Freeman, who served from 1955 to 1998. Later, the communications and fine arts center was named after Cook. and the honors program was later partially named in his honor.

1997-2004

Lomax’s background included serving for 20 years as an elected member of the Board of Commissioners in Fulton County, Georgia. He also founded the National Black Arts Festival as well as the Amistad Corporation. Lomax also played a key role in attracting the 1996 Olympic Games to Atlanta. Most notably, the Morehouse alumnus taught literature at his alma mater, Spelman College, the Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of Georgia. He also served as president of The National Faculty.

Lomax led an aggressive campaign to renovate and modernize campus facilities and to also improve the University’s profile. He led a $60 million campus renovation program to focus on students’ living and learning environments, and Lomax added the Dillard University International Center for Economic Freedom (DUICEF, now known as Michael and Shaun Jones Hall or Jones Hall) to the campus landscape in 2004. Enrollment increased 49 percent, reaching more than 2,200 students from the U.S., the Caribbean and Africa. Having also tripled alumni, individual, corporate and foundation giving, Lomax helped Dillard reach a U.S. News & World Report ranking of 20th in the top tier of colleges and universities in the South by 2002.

Lomax led an aggressive campaign to renovate and modernize campus facilities and to also improve the University’s profile. He led a $60 million campus renovation program to focus on students’ living and learning environments, and Lomax added the Dillard University International Center for Economic Freedom (DUICEF, now known as Michael and Shaun Jones Hall or Jones Hall) to the campus landscape in 2004. Enrollment increased 49 percent, reaching more than 2,200 students from the U.S., the Caribbean and Africa. Having also tripled alumni, individual, corporate and foundation giving, Lomax helped Dillard reach a U.S. News & World Report ranking of 20th in the top tier of colleges and universities in the South by 2002.

In 2004, Lomax decided that it was time to move on to a new assignment. He accepted the position of chief executive officer and president of the United Negro College Fund. Dr. Bettye Parker Smith served as the interim president until the arrival of a leader who would be called on to shepherd Dillard through its most challenging period since opening the doors of the Gentilly campus.

2005-2011

Hughes had served in administrative positions at Florida Presbyterian College (now Eckerd College), the University of Minnesota, the University of Toledo, Arizona State University and San Diego State University before becoming president of California State University, Stanislaus where she increased enrollment, fundraising and capital construction. Her efforts led to the university climbing national rankings.

Barely allowed to settle in at Dillard, Hughes was faced with the threat of Hurricane Katrina only one month after beginning her tenure. As the storm approached the area and a mandatory evacuation had been ordered by the City of New Orleans, Hughes acted quickly to get the students to safety by having them transported to Shreveport. In a savvy move, Hughes later negotiated a deal with the Hilton New Orleans Riverside to continue operations and instruction there as the recovery process began on campus.

Barely allowed to settle in at Dillard, Hughes was faced with the threat of Hurricane Katrina only one month after beginning her tenure. As the storm approached the area and a mandatory evacuation had been ordered by the City of New Orleans, Hughes acted quickly to get the students to safety by having them transported to Shreveport. In a savvy move, Hughes later negotiated a deal with the Hilton New Orleans Riverside to continue operations and instruction there as the recovery process began on campus.

With unwavering determination, Hughes facilitated the rebuilding of Dillard’s historic, 55-acre campus which had lost more than $400 million to physical damage and business interruption. In the first year of Hughes’ tenure, and again in 2006, the University raised more than $34 million in public and private gifts and grants, far exceeding any previous annual total in Dillard’s history.

In 2007, Dillard devised a comprehensive strategic plan to hasten recovery and guide the school’s future. The following year, Dillard launched its first capital campaign, Advantage Dillard!, with a goal of raising $70 million for six priority areas: increasing student scholarships; enhancing teaching, learning, and campus facilities; introducing cutting-edge technology; enhancing the library; strengthening general program support; and securing Dillard’s future through general endowment. More than $60 million has been raised to date.

Following the Class of 2010’s commencement exercises, Hughes cut the ribbons for two exciting new facilities, the Professional Schools and Sciences Building and the Student Union and Health and Wellness Center. Both buildings are LEED® (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) registered, exemplifying Dillard’s burgeoning commitment to sustainability and environmental initiatives.

During the summer of 2010, Hughes announced an academic restructuring of the University under a new four-college system with 22 majors that will position Dillard to capitalize on future growth opportunities. The College of General Studies – designed as a two-year gateway program for all incoming freshmen to improve graduation rates, would enhance preparation for majors, and foster kinship among students – now stands alongside the College of Arts and Sciences, the College of Professional Studies, and the College of Business. Hughes transitioned from the presidency in June 2011 and Dr. James Lyons served as interim president.

2012-2022

The son of a United Methodist Church minister, Kimbrough felt a connection with Dillard as a UMC school. One of Kimbrough’s strengths has been his ability to keep up with and utilize social media, which had grown too rapidly for traditional higher education leaders. Living up to his moniker, Kimbrough has leveraged hip hop culture to teach his students ethics and leadership.

Kimbrough’s dynamic presence and social capital has attracted some of the most recognized figures of the day to Dillard as visitors and lecturers. His “Brain Food” lecture series hosted such figures as Michael Eric Dyson, Kirk Franklin, Juan Williams, the controversial Candace Owens, Malcolm Nance, Gabrielle Union and Issa Rae. In 2019, the series featured Dillard alumni as part of the University’s 150th anniversary celebration: Dr. Nita Landry, Jericho Brown and Lisa Frazier-Page. The Revius O. Ortique Jr. Lecture on Law and Society attracted Bryan Stevenson, Angela Rye, former attorney general Eric Holder, James Forman Jr. and Dillard alumnus Michael D. Jones. Also impressive was the list of commencement speakers who have visited the Oaks during Kimbrough’s presidency: First Lady Michelle Obama, Jeff Johnson, Terrence J, Janelle Monáe, Chance the Rapper, Regina Hall, Michael Ealy and Denzel Washington whose address went viral on social media.

Kimbrough’s dynamic presence and social capital has attracted some of the most recognized figures of the day to Dillard as visitors and lecturers. His “Brain Food” lecture series hosted such figures as Michael Eric Dyson, Kirk Franklin, Juan Williams, the controversial Candace Owens, Malcolm Nance, Gabrielle Union and Issa Rae. In 2019, the series featured Dillard alumni as part of the University’s 150th anniversary celebration: Dr. Nita Landry, Jericho Brown and Lisa Frazier-Page. The Revius O. Ortique Jr. Lecture on Law and Society attracted Bryan Stevenson, Angela Rye, former attorney general Eric Holder, James Forman Jr. and Dillard alumnus Michael D. Jones. Also impressive was the list of commencement speakers who have visited the Oaks during Kimbrough’s presidency: First Lady Michelle Obama, Jeff Johnson, Terrence J, Janelle Monáe, Chance the Rapper, Regina Hall, Michael Ealy and Denzel Washington whose address went viral on social media.

Dillard’s fundraising has flourished during Kimbrough’s administration. One of his most significant accomplishments was having a $160 million Hurricane Katrina loan from the federal government forgiven in 2018. That paved the way for the University’s endowment to grow from $48 million to $105 million. Also impressive was the alumni giving rate reaching 23 percent. In an almost poetic move, the University found a way to leverage social media to increase its fundraising efforts. Dillard turned its attention to GivingTuesday, a day of online giving which brought in over $64,000 in 24 hours on the University’s first try. By 2020, Dillard had managed to increase its GivingTuesday total to over $780,000 despite battling the COVID-19 pandemic.

Academically, Kimbrough turned his attention to several programs that he felt would bring Dillard attention. In 2012, the University introduced its film studies program, a response to the number of “Hollywood South” film and television productions in Louisiana. By 2018, Dillard’s physics program had become known for being a top producer of African American physics graduates. The University also began to experience success in its pre-law program. In 2021, 93 percent of the pre-law students who applied for law schools had been accepted. Feeling that his work at Dillard had been done, Kimbrough announced in August of 2021 that he would hand off the “leadership baton” as of May of 2022.

2022-2024

The university welcomed its first cohort of masters of nursing graduate students, earned Gold Certification from the CEO Roundtable on Cancer, secured federal funding to battle gender-based violence, and launched partnerships to advance the business of the energy evolution.

The university welcomed its first cohort of masters of nursing graduate students, earned Gold Certification from the CEO Roundtable on Cancer, secured federal funding to battle gender-based violence, and launched partnerships to advance the business of the energy evolution.

Strengthening the University’s physical infrastructure to enhance durability and the student experience was one of Dr. Ford’s top objectives. As a result, she led the university in investing millions of dollars in external funding to restore the electrical dual loop system, replace six roofs, bring the campus into ADA compliance, create a legacy walk, complete a master plan, begin construction on a new living-learning-serving community, and commence renovations on Alumni House, Howard House, Andrew Young home, Dent Hall, and Lawless Memorial Chapel.

Dillard University re-established intercollegiate NAIA baseball and softball programs. Dillard student athletes won GCAC conference championships in baseball, track and field, and cross-country, and the Bleu Devil tennis and track and field team members placed nationally. The Dillard University Concert Choir and female ensemble resumed their annual national tour performing at the Kennedy Center and at the Syracuse Jazz Fest. The study abroad program relaunched with new university partnerships in Japan and China.

To enhance campus cohesiveness, displays of the new mission statement were installed in all classrooms, and Dr. Ford established a staff council, an internal e-newsletter called the DU Roux, an external newsletter called the Dillard Digest, tenure and promotion celebration dinners, and new faculty and staff receptions.

In January 2023, Dr. Ford re-established the National Center for Black Jewish Relations, hosting a series of events to combat racism and anti-semitism, and promote understanding between Black and Jewish communities.

The Dillard University Alumni Association established new chapters in Florida and Indiana and increased their giving of time, talent and treasure significantly.

In the 2023-2024 academic year, the University exceeded its advancement goals by 156%, securing more than $10.7 million in public sponsored programs, a $850,000 Federal Community Funding Program sponsored by Congressman Troy Carter and Senator Bill Cassidy, and $7.12 million from private sources including the United Methodist Church, Humana, Healthy Blue and a $1.2 million gift from the Helen Harris Trust.

Leveraging UNCF Transformation funding in 2023, Dillard University established an office of sustainability, which created a recycling program, implemented beautification programs, supported the DU Bleu Green Krewe, and secured multiple federal grants.

In 2024 under the joint leadership of President Ford and Interim President Dr. Monique Guillory, the US Environmental Protection Agency awarded Dillard University, in partnership with the United Way of Southeast Louisiana, a $19.9 million Community Change Grant to improve sustainability, energy efficiencies and resilience on campus and in the community.

Also in 2024, the New Orleans Super Bowl LIX Host Committee partnered with Dillard University to promote supplier diversity certification and engagement opportunities.

Complete the form below and provide as many details as you can. The OCM photography team will notify you by email when your request has been received along with the timeline to expect your update. ALLOW 2 WEEKS MINIMUM FOR UPDATES. (PLEASE, NO LAST-MINUTE REQUESTS.) Some requests require more time. For upcoming events, please include the event name, date, time, location along with a description of the event. THIS FORM IS FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY.

Please allow 2 weeks for your request to be completed. We will reach out regarding updates.